Atlantis

Atlantis

| Part of a series on |

| Platonism |

|---|

|

| Allegories and metaphors |

| Related articles |

| Related categories |

Atlantis (Ancient Greek: Ἀτλαντὶς νῆσος, Atlantis nesos, "island of Atlas") is a fictional island mentioned in an allegory on the hubris of nations in Plato's works Timaeus and Critias, wherein it represents the antagonist naval power that besieges "Ancient Athens", the pseudo-historic embodiment of Plato's ideal state in The Republic.[1] In the story, Athens repels the Atlantean attack unlike any other nation of the known world,[2] supposedly bearing witness to the superiority of Plato's concept of a state.[3][4] The story concludes with Atlantis falling out of favor with the deities and submerging into the Atlantic Ocean.

Despite its minor importance in Plato's work, the Atlantis story has had a considerable impact on literature. The allegorical aspect of Atlantis was taken up in utopian works of several Renaissance writers, such as Francis Bacon's New Atlantis and Thomas More's Utopia.[5][6] On the other hand, nineteenth-century amateur scholars misinterpreted Plato's narrative as historical tradition, most famously Ignatius L. Donnelly in his Atlantis: The Antediluvian World. Plato's vague indications of the time of the events (more than 9,000 years before his time[7]) and the alleged location of Atlantis ("beyond the Pillars of Hercules") gave rise to much pseudoscientific speculation.[8] As a consequence, Atlantis has become a byword for any and all supposed advanced prehistoric lost civilizations and continues to inspire contemporary fiction, from comic books to films.

While present-day philologists and classicists agree on the story's fictional character,[9][10] there is still debate on what served as its inspiration. Plato is known to have freely borrowed some of his allegories and metaphors from older traditions, as he did, for instance, with the story of Gyges.[11] This led a number of scholars to investigate possible inspiration of Atlantis from Egyptian records of the Thera eruption,[12][13] the Sea Peoples invasion,[14] or the Trojan War.[15] Others have rejected this chain of tradition as implausible and insist that Plato created an entirely fictional account,[16][17][18] drawing loose inspiration from contemporary events such as the failed Athenian invasion of Sicily in 415–413 BC or the destruction of Helike in 373 BC.[19]

Plato's dialogues

Timaeus

The only primary sources for Atlantis are Plato's dialogues Timaeus and Critias; all other mentions of the island are based on them. The dialogues claim to quote Solon, who visited Egypt between 590 and 580 BC; they state that he translated Egyptian records of Atlantis.[20] Written in 360 BC, Plato introduced Atlantis in Timaeus:

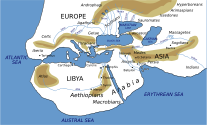

For it is related in our records how once upon a time your State stayed the course of a mighty host, which, starting from a distant point in the Atlantic ocean, was insolently advancing to attack the whole of Europe, and Asia to boot. For the ocean there was at that time navigable; for in front of the mouth which you Greeks call, as you say, 'the pillars of Heracles,' there lay an island which was larger than Libya and Asia together; and it was possible for the travelers of that time to cross from it to the other islands, and from the islands to the whole of the continent over against them which encompasses that veritable ocean. For all that we have here, lying within the mouth of which we speak, is evidently a haven having a narrow entrance; but that yonder is a real ocean, and the land surrounding it may most rightly be called, in the fullest and truest sense, a continent. Now in this island of Atlantis there existed a confederation of kings, of great and marvelous power, which held sway over all the island, and over many other islands also and parts of the continent.[21]

The four people appearing in those two dialogues are the politicians Critias and Hermocrates as well as the philosophers Socrates and Timaeus of Locri, although only Critias speaks of Atlantis. In his works Plato makes extensive use of the Socratic method in order to discuss contrary positions within the context of a supposition.

The Timaeus begins with an introduction, followed by an account of the creations and structure of the universe and ancient civilizations. In the introduction, Socrates muses about the perfect society, described in Plato's Republic (c. 380 BC), and wonders if he and his guests might recollect a story which exemplifies such a society. Critias mentions a tale he considered to be historical, that would make the perfect example, and he then follows by describing Atlantis as is recorded in the Critias. In his account, ancient Athens seems to represent the "perfect society" and Atlantis its opponent, representing the very antithesis of the "perfect" traits described in the Republic.

Critias

According to Critias, the Hellenic deities of old divided the land so that each deity might have their own lot; Poseidon was appropriately, and to his liking, bequeathed the island of Atlantis. The island was larger than Ancient Libya and Asia Minor combined,[22][23] but it was later sunk by an earthquake and became an impassable mud shoal, inhibiting travel to any part of the ocean. Plato asserted that the Egyptians described Atlantis as an island consisting mostly of mountains in the northern portions and along the shore and encompassing a great plain in an oblong shape in the south "extending in one direction three thousand stadia [about 555 km; 345 mi], but across the center inland it was two thousand stadia [about 370 km; 230 mi]." Fifty stadia [9 km; 6 mi] from the coast was a mountain that was low on all sides ... broke it off all round about ... the central island itself was five stades in diameter [about 0.92 km; 0.57 mi].

In Plato's metaphorical tale, Poseidon fell in love with Cleito, the daughter of Evenor and Leucippe, who bore him five pairs of male twins. The eldest of these, Atlas, was made rightful king of the entire island and the ocean (called the Atlantic Ocean in his honor), and was given the mountain of his birth and the surrounding area as his fiefdom. Atlas's twin Gadeirus, or Eumelus in Greek, was given the extremity of the island toward the pillars of Hercules.[24] The other four pairs of twins—Ampheres and Evaemon, Mneseus and Autochthon, Elasippus and Mestor, and Azaes and Diaprepes—were also given "rule over many men, and a large territory."

Poseidon carved the mountain where his love dwelt into a palace and enclosed it with three circular moats of increasing width, varying from one to three stadia and separated by rings of land proportional in size. The Atlanteans then built bridges northward from the mountain, making a route to the rest of the island. They dug a great canal to the sea, and alongside the bridges carved tunnels into the rings of rock so that ships could pass into the city around the mountain; they carved docks from the rock walls of the moats. Every passage to the city was guarded by gates and towers, and a wall surrounded each ring of the city. The walls were constructed of red, white, and black rock, quarried from the moats, and were covered with brass, tin, and the precious metal orichalcum, respectively.

According to Critias, 9,000 years before his lifetime a war took place between those outside the Pillars of Hercules at the Strait of Gibraltar and those who dwelt within them. The Atlanteans had conquered the parts of Libya within the Pillars of Hercules, as far as Egypt, and the European continent as far as Tyrrhenia, and had subjected its people to slavery. The Athenians led an alliance of resistors against the Atlantean empire, and as the alliance disintegrated, prevailed alone against the empire, liberating the occupied lands.

But afterwards there occurred violent earthquakes and floods; and in a single day and night of misfortune all your warlike men in a body sank into the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner disappeared in the depths of the sea. For which reason the sea in those parts is impassable and impenetrable, because there is a shoal of mud in the way; and this was caused by the subsidence of the island.[25]

The logographer Hellanicus of Lesbos wrote an earlier work entitled Atlantis, of which only a few fragments survive. Hellanicus' work appears to have been a genealogical one concerning the daughters of Atlas (Ἀτλαντὶς in Greek means "of Atlas"),[12] but some authors have suggested a possible connection with Plato's island. John V. Luce notes that when Plato writes about the genealogy of Atlantis's kings, he writes in the same style as Hellanicus, suggesting a similarity between a fragment of Hellanicus's work and an account in the Critias.[12] Rodney Castleden suggests that Plato may have borrowed his title from Hellanicus, who may have based his work on an earlier work about Atlantis.[26]

Castleden has pointed out that Plato wrote of Atlantis in 359 BC, when he returned to Athens from Sicily. He notes a number of parallels between the physical organisation and fortifications of Syracuse and Plato's description of Atlantis.[27] Gunnar Rudberg was the first who elaborated upon the idea that Plato's attempt to realize his political ideas in the city of Syracuse could have heavily inspired the Atlantis account.[28]

Interpretations

Ancient

Some ancient writers viewed Atlantis as fictional or metaphorical myth; others believed it to be real.[29] Aristotle believed that Plato, his teacher, had invented the island to teach philosophy.[20] The philosopher Crantor, a student of Plato's student Xenocrates, is cited often as an example of a writer who thought the story to be historical fact. His work, a commentary on Timaeus, is lost, but Proclus, a Neoplatonist of the fifth century AD, reports on it.[30] The passage in question has been represented in the modern literature either as claiming that Crantor visited Egypt, had conversations with priests, and saw hieroglyphs confirming the story, or, as claiming that he learned about them from other visitors to Egypt.[31] Proclus wrote:

As for the whole of this account of the Atlanteans, some say that it is unadorned history, such as Crantor, the first commentator on Plato. Crantor also says that Plato's contemporaries used to criticize him jokingly for not being the inventor of his Republic but copying the institutions of the Egyptians. Plato took these critics seriously enough to assign to the Egyptians this story about the Athenians and Atlanteans, so as to make them say that the Athenians really once lived according to that system.

The next sentence is often translated "Crantor adds, that this is testified by the prophets of the Egyptians, who assert that these particulars [which are narrated by Plato] are written on pillars which are still preserved." But in the original, the sentence starts not with the name Crantor but with the ambiguous He; whether this referred to Crantor or to Plato is the subject of considerable debate. Proponents of both Atlantis as a metaphorical myth and Atlantis as history have argued that the pronoun refers to Crantor.[32]

Alan Cameron argues that the pronoun should be interpreted as referring to Plato, and that, when Proclus writes that "we must bear in mind concerning this whole feat of the Athenians, that it is neither a mere myth nor unadorned history, although some take it as history and others as myth", he is treating "Crantor's view as mere personal opinion, nothing more; in fact he first quotes and then dismisses it as representing one of the two unacceptable extremes".[33]

Cameron also points out that whether he refers to Plato or to Crantor, the statement does not support conclusions such as Otto Muck's "Crantor came to Sais and saw there in the temple of Neith the column, completely covered with hieroglyphs, on which the history of Atlantis was recorded. Scholars translated it for him, and he testified that their account fully agreed with Plato's account of Atlantis"[34] or J. V. Luce's suggestion that Crantor sent "a special enquiry to Egypt" and that he may simply be referring to Plato's own claims.[33]

Another passage from the commentary by Proclus on the "Timaeus" gives a description of the geography of Atlantis:

That an island of such nature and size once existed is evident from what is said by certain authors who investigated the things around the outer sea. For according to them, there were seven islands in that sea in their time, sacred to Persephone, and also three others of enormous size, one of which was sacred to Hades, another to Ammon, and another one between them to Poseidon, the extent of which was a thousand stadia [200 km]; and the inhabitants of it—they add—preserved the remembrance from their ancestors of the immeasurably large island of Atlantis which had really existed there and which for many ages had reigned over all islands in the Atlantic sea and which itself had like-wise been sacred to Poseidon. Now these things Marcellus has written in his Aethiopica.[35]

Marcellus remains unidentified.

Other ancient historians and philosophers who believed in the existence of Atlantis were Strabo and Posidonius.[36] Some have theorized that, before the sixth century BC, the "Pillars of Hercules" may have applied to mountains on either side of the Gulf of Laconia, and also may have been part of the pillar cult of the Aegean.[37][38] The mountains stood at either side of the southernmost gulf in Greece, the largest in the Peloponnese, and it opens onto the Mediterranean Sea. This would have placed Atlantis in the Mediterranean, lending credence to many details in Plato's discussion.

The fourth-century historian Ammianus Marcellinus, relying on a lost work by Timagenes, a historian writing in the first century BC, writes that the Druids of Gaul said that part of the inhabitants of Gaul had migrated there from distant islands. Some have understood Ammianus's testimony as a claim that at the time of Atlantis's sinking into the sea, its inhabitants fled to western Europe; but Ammianus, in fact, says that "the Drasidae (Druids) recall that a part of the population is indigenous but others also migrated in from islands and lands beyond the Rhine" (Res Gestae 15.9), an indication that the immigrants came to Gaul from the north (Britain, the Netherlands, or Germany), not from a theorized location in the Atlantic Ocean to the south-west.[39] Instead, the Celts who dwelled along the ocean were reported to venerate twin gods, (Dioscori), who appeared to them coming from that ocean.[40]

Jewish and Christian

During the early first century, the Hellenistic Jewish philosopher Philo wrote about the destruction of Atlantis in his On the Eternity of the World, xxvi. 141, in a longer passage allegedly citing Aristotle's successor Theophrastus:[41]

... And the island of Atalantes [translator's spelling; original: "Ἀτλαντίς"] which was greater than Africa and Asia, as Plato says in the Timaeus, in one day and night was overwhelmed beneath the sea in consequence of an extraordinary earthquake and inundation and suddenly disappeared, becoming sea, not indeed navigable, but full of gulfs and eddies.[42]

The theologian Joseph Barber Lightfoot (Apostolic Fathers, 1885, II, p. 84) noted on this passage: "Clement may possibly be referring to some known, but hardly accessible land, lying without the pillars of Hercules. But more probably he contemplated some unknown land in the far west beyond the ocean, like the fabled Atlantis of Plato ..."[43]

Other early Christian writers wrote about Atlantis, although they had mixed views on whether it once existed or was an untrustworthy myth of pagan origin.[44] Tertullian believed Atlantis was once real and wrote that in the Atlantic Ocean once existed "[the isle] that was equal in size to Libya or Asia"[45] referring to Plato's geographical description of Atlantis. The early Christian apologist writer Arnobius also believed Atlantis once existed, but blamed its destruction on pagans.[46]

Cosmas Indicopleustes in the sixth century wrote of Atlantis in his Christian Topography in an attempt to prove his theory that the world was flat and surrounded by water:[47][page needed]

... In like manner the philosopher Timaeus also describes this Earth as surrounded by the Ocean, and the Ocean as surrounded by the more remote earth. For he supposes that there is to westward an island, Atlantis, lying out in the Ocean, in the direction of Gadeira (Cadiz), of an enormous magnitude, and relates that the ten kings having procured mercenaries from the nations in this island came from the earth far away, and conquered Europe and Asia, but were afterwards conquered by the Athenians, while that island itself was submerged by God under the sea. Both Plato and Aristotle praise this philosopher, and Proclus has written a commentary on him. He himself expresses views similar to our own with some modifications, transferring the scene of the events from the east to the west. Moreover he mentions those ten generations as well as that earth which lies beyond the Ocean. And in a word it is evident that all of them borrow from Moses, and publish his statements as their own.[48]

Modern

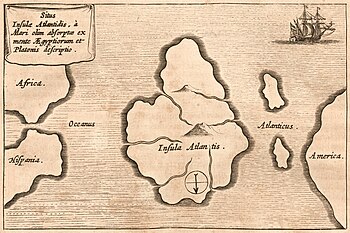

Aside from Plato's original account, modern interpretations regarding Atlantis are an amalgamation of diverse, speculative movements that began in the sixteenth century,[50] when scholars began to identify Atlantis with the New World. Francisco Lopez de Gomara was the first to state that Plato was referring to America, as did Francis Bacon and Alexander von Humboldt; Janus Joannes Bircherod said in 1663 orbe novo non-novo ("the New World is not new"). Athanasius Kircher accepted Plato's account as literally true, describing Atlantis as a small continent in the Atlantic Ocean.[20]

Contemporary perceptions of Atlantis share roots with Mayanism, which can be traced to the beginning of the Modern Age, when European imaginations were fueled by their initial encounters with the indigenous peoples of the Americas.[51] From this era sprang apocalyptic and utopian visions that would inspire many subsequent generations of theorists.[51]

Most of these interpretations are considered pseudohistory, pseudoscience, or pseudoarchaeology, as they have presented their works as academic or scientific, but lack the standards or criteria.

The Flemish cartographer and geographer Abraham Ortelius is believed to have been the first person to imagine that the continents were joined before drifting to their present positions. In the 1596 edition of his Thesaurus Geographicus he wrote: "Unless it be a fable, the island of Gadir or Gades [Cadiz] will be the remaining part of the island of Atlantis or America, which was not sunk (as Plato reports in the Timaeus) so much as torn away from Europe and Africa by earthquakes and flood... The traces of the ruptures are shown by the projections of Europe and Africa and the indentations of America in the parts of the coasts of these three said lands that face each other to anyone who, using a map of the world, carefully considered them. So that anyone may say with Strabo in Book 2, that what Plato says of the island of Atlantis on the authority of Solon is not a figment."[52]

Atlantis pseudohistory

Early influential literature

The term "utopia" (from "no place") was coined by Sir Thomas More in his sixteenth-century work of fiction Utopia.[53] Inspired by Plato's Atlantis and travelers' accounts of the Americas, More described an imaginary land set in the New World.[54] His idealistic vision established a connection between the Americas and utopian societies, a theme that Bacon discussed in The New Atlantis (c. 1623).[51] A character in the narrative gives a history of Atlantis that is similar to Plato's and places Atlantis in America. People had begun believing that the Mayan and Aztec ruins could possibly be the remnants of Atlantis.[53]

Impact of Mayanism

Much speculation began as to the origins of the Maya, which led to a variety of narratives and publications that tried to rationalize the discoveries within the context of the Bible and that had undertones of racism in their connections between the Old and New World. The Europeans believed the indigenous people to be inferior and incapable of building that which was now in ruins and by sharing a common history, they insinuate that another race must have been responsible.

In the middle and late nineteenth century, several renowned Mesoamerican scholars, starting with Charles Etienne Brasseur de Bourbourg, and including Edward Herbert Thompson and Augustus Le Plongeon, formally proposed that Atlantis was somehow related to Mayan and Aztec culture.

The French scholar Brasseur de Bourbourg traveled extensively through Mesoamerica in the mid-1800s, and was renowned for his translations of Mayan texts, most notably the sacred book Popol Vuh, as well as a comprehensive history of the region. Soon after these publications, however, Brasseur de Bourbourg lost his academic credibility, due to his claim that the Maya peoples had descended from the Toltecs, people he believed were the surviving population of the racially superior civilization of Atlantis.[55] His work combined with the skillful, romantic illustrations of Jean Frederic Waldeck, which visually alluded to Egypt and other aspects of the Old World, created an authoritative fantasy that excited much interest in the connections between worlds.

Inspired by Brasseur de Bourbourg's diffusion theories, the pseudoarchaeologist Augustus Le Plongeon traveled to Mesoamerica and performed some of the first excavations of many famous Mayan ruins. Le Plongeon invented narratives, such as the kingdom of Mu saga, which romantically drew connections to him, his wife Alice, and Egyptian deities Osiris and Isis, as well as to Heinrich Schliemann, who had just discovered the ancient city of Troy from Homer's epic poetry (that had been described as merely mythical).[56][page range too broad] He also believed that he had found connections between the Greek and Mayan languages, which produced a narrative of the destruction of Atlantis.[57]

Ignatius Donnelly

The 1882 publication of Atlantis: the Antediluvian World by Ignatius L. Donnelly stimulated much popular interest in Atlantis. He was greatly inspired by early works in Mayanism, and like them, attempted to establish that all known ancient civilizations were descended from Atlantis, which he saw as a technologically sophisticated, more advanced culture. Donnelly drew parallels between creation stories in the Old and New Worlds, attributing the connections to Atlantis, where he believed the Biblical Garden of Eden existed.[58] As implied by the title of his book, he also believed that Atlantis was destroyed by the Great Flood mentioned in the Bible.

Donnelly is credited as the "father of the nineteenth century Atlantis revival" and is the reason the myth endures today.[59] He unintentionally promoted an alternative method of inquiry to history and science, and the idea that myths contain hidden information that opens them to "ingenious" interpretation by people who believe they have new or special insight.[60]

Madame Blavatsky and the Theosophists

The Russian mystic Helena Petrovna Blavatsky and her partner Henry Steel Olcott founded their Theosophical Society in the 1870s with a philosophy that combined western romanticism and eastern religious concepts. Blavatsky and her followers in this group are often cited as the founders of New Age and other spiritual movements.[53]

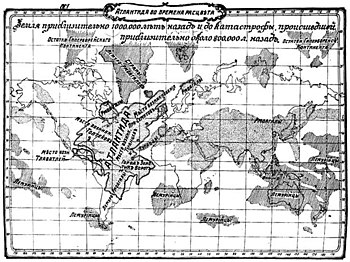

Blavatsky took up Donnelly's interpretations when she wrote The Secret Doctrine (1888), which she claimed was originally dictated in Atlantis. She maintained that the Atlanteans were cultural heroes (contrary to Plato, who describes them mainly as a military threat). She believed in a form of racial evolution (as opposed to primate evolution). In her process of evolution the Atlanteans were the fourth "Root Race", which were succeeded by the fifth, the "Aryan race", which she identified with the modern human race.[53]

The Theosophists believed that the civilization of Atlantis reached its peak between 1,000,000 and 900,000 years ago, but destroyed itself through internal warfare brought about by the dangerous use of psychic and supernatural powers of the inhabitants. Rudolf Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy and Waldorf Schools, along with other well known Theosophists, such as Annie Besant, also wrote of cultural evolution in much the same vein. Some subsequent occultists have followed Blavatsky, at least to the point of tracing the lineage of occult practices back to Atlantis. Among the most famous is Dion Fortune in her Esoteric Orders and Their Work.[61]

Drawing on the ideas of Rudolf Steiner and Hanns Hörbiger, Egon Friedell started his book Kulturgeschichte des Altertums, and thus his historical analysis of antiquity, with the ancient culture of Atlantis. The book was published in 1940.

Nazism and occultism

Blavatsky was also inspired by the work of the 18th-century astronomer Jean-Sylvain Bailly, who had "Orientalized" the Atlantis myth in his mythical continent of Hyperborea, a reference to Greek myths featuring a Northern European region of the same name, home to a giant, godlike race.[62][63] Dan Edelstein claims that her reshaping of this theory in The Secret Doctrine provided the Nazis with a mythological precedent and a pretext for their ideological platform and their subsequent genocide.[62] However, Blavatsky's writings mention that the Atlantean were in fact olive-skinned peoples with Mongoloid traits who were the ancestors of modern Native Americans, Mongolians, and Malayans.[64][65][66]

The idea that the Atlanteans were Hyperborean, Nordic supermen who originated in the Northern Atlantic or even in the far North, was popular in the German ariosophic movement around 1900, propagated by Guido von List and others.[67] It gave its name to the Thule Gesellschaft, an antisemite Münich lodge, which preceded the German Nazi Party (see Thule). The scholars Karl Georg Zschaetzsch (1920) and Herman Wirth (1928) were the first to speak of a "Nordic-Atlantean" or "Aryan-Nordic" master race that spread from Atlantis over the Northern Hemisphere and beyond. The Hyperboreans were contrasted with the Jewish people. Party ideologist Alfred Rosenberg (in The Myth of the Twentieth Century, 1930) and SS-leader Heinrich Himmler made it part of the official doctrine.[68] The idea was followed up by the adherents of Esoteric Nazism such as Julius Evola (1934) and, more recently, Miguel Serrano (1978).

The idea of Atlantis as the homeland of the Caucasian race would contradict the beliefs of older Esoteric and Theosophic groups, which taught that the Atlanteans were non-Caucasian brown-skinned peoples. Modern Esoteric groups, including the Theosophic Society, do not consider Atlantean society to have been superior or Utopian—they rather consider it a lower stage of evolution.[69]

Edgar Cayce

The clairvoyant Edgar Cayce spoke frequently of Atlantis. During his "life readings", he claimed that many of his subjects were reincarnations of people who had lived there. By tapping into their collective consciousness, the "Akashic Records" (a term borrowed from Theosophy),[70] Cayce declared that he was able to give detailed descriptions of the lost continent.[71] He also asserted that Atlantis would "rise" again in the 1960s (sparking much popularity of the myth in that decade) and that there is a "Hall of Records" beneath the Egyptian Sphinx which holds the historical texts of Atlantis.

Recent times

As continental drift became widely accepted during the 1960s, and the increased understanding of plate tectonics demonstrated the impossibility of a lost continent in the geologically recent past,[72] most "Lost Continent" theories of Atlantis began to wane in popularity.

Plato scholar Julia Annas, Regents Professor of Philosophy at the University of Arizona, had this to say on the matter:

The continuing industry of discovering Atlantis illustrates the dangers of reading Plato. For he is clearly using what has become a standard device of fiction—stressing the historicity of an event (and the discovery of hitherto unknown authorities) as an indication that what follows is fiction. The idea is that we should use the story to examine our ideas of government and power. We have missed the point if instead of thinking about these issues we go off exploring the sea bed. The continuing misunderstanding of Plato as historian here enables us to see why his distrust of imaginative writing is sometimes justified.[73]

One of the proposed explanations for the historical context of the Atlantis story is a warning of Plato to his contemporary fourth-century fellow-citizens against their striving for naval power.[18]

Kenneth Feder points out that Critias's story in the Timaeus provides a major clue. In the dialogue, Critias says, referring to Socrates' hypothetical society:

And when you were speaking yesterday about your city and citizens, the tale which I have just been repeating to you came into my mind, and I remarked with astonishment how, by some mysterious coincidence, you agreed in almost every particular with the narrative of Solon. ...[74]

Feder quotes A. E. Taylor, who wrote, "We could not be told much more plainly that the whole narrative of Solon's conversation with the priests and his intention of writing the poem about Atlantis are an invention of Plato's fancy."[75]

Location hypotheses

Since Donnelly's day, there have been dozens of locations proposed for Atlantis, to the point where the name has become a generic concept, divorced from the specifics of Plato's account. This is reflected in the fact that many proposed sites are not within the Atlantic at all. Few today are scholarly or archaeological hypotheses, while others have been made by psychic (e.g., Edgar Cayce) or other pseudoscientific means. (The Atlantis researchers Jacques Collina-Girard and Georgeos Díaz-Montexano, for instance, each claim the other's hypothesis is pseudoscience.)[76] Many of the proposed sites share some of the characteristics of the Atlantis story (water, catastrophic end, relevant time period), but none has been demonstrated to be a true historical Atlantis.

In or near the Mediterranean Sea

Most of the historically proposed locations are in or near the Mediterranean Sea: islands such as Sardinia,[77][78][79] Crete, Santorini (Thera), Sicily, Cyprus, and Malta; land-based cities or states such as Troy,[80][page needed] Tartessos, and Tantalis (in the province of Manisa, Turkey);[81] Israel-Sinai or Canaan;[citation needed] and northwestern Africa.[82]

The Thera eruption, dated to the seventeenth or sixteenth century BC, caused a large tsunami that some experts hypothesize devastated the Minoan civilization on the nearby island of Crete, further leading some to believe that this may have been the catastrophe that inspired the story.[83][84] In the area of the Black Sea the following locations have been proposed: Bosporus and Ancomah (a legendary place near Trabzon).

Others have noted that, before the sixth century BC, the mountains on either side of the Gulf of Laconia were called the "Pillars of Hercules",[37][38] and they could be the geographical location being described in ancient reports upon which Plato was basing his story. The mountains stood at either side of the southernmost gulf in Greece, the largest in the Peloponnese, and that gulf opens onto the Mediterranean Sea. If from the beginning of discussions, misinterpretation of Gibraltar as the location rather than being at the Gulf of Laconia, would lend itself to many erroneous concepts regarding the location of Atlantis. Plato may have not been aware of the difference. The Laconian pillars open to the south toward Crete and beyond which is Egypt. The Thera eruption and the Late Bronze Age collapse affected that area and might have been the devastation to which the sources used by Plato referred. Significant events such as these would have been likely material for tales passed from one generation to another for almost a thousand years.

댓글

댓글 쓰기